With a background in robotics and the Internet of Things, James Maitland has spent his career at the intersection of technology and medicine. He brings a unique perspective to one of the most pressing challenges in health tech today: how to regulate the powerful, ever-evolving artificial intelligence being integrated into medical devices. As the FDA sifts through more than 100 comments from a spectrum of stakeholders, the path forward remains unclear, caught between the industry’s plea for flexibility and patients’ demand for transparency.

This conversation explores the complex middle ground the FDA must navigate. We delve into the practical realities of monitoring different types of AI, the profound responsibility that falls on manufacturers to support healthcare providers, especially those in under-resourced areas, and the critical need to redefine “performance” to include the real, lived experiences of patients. Ultimately, it’s a look at how to build a regulatory framework that fosters trust and innovation in equal measure.

Industry groups like AdvaMed advocate for a risk-based approach using existing frameworks. Can you walk us through the practical differences in monitoring a low-risk “locked” AI model versus a high-risk “continual machine learning” model, providing specific metrics for each?

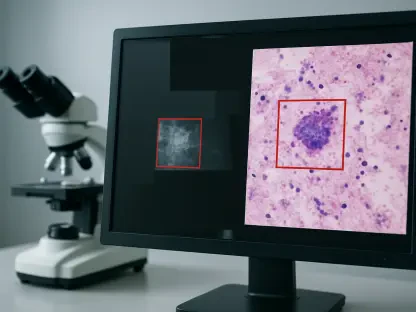

Absolutely, and this distinction is at the heart of the industry’s argument. A “locked” AI model is essentially a fixed algorithm. Once it’s validated and deployed, it doesn’t change on its own. Think of it like a static piece of software. Monitoring it is a more traditional postmarket surveillance activity, falling neatly under existing Quality Management System Regulations. We’re looking for signs that its performance in the real world is deviating from the clinical trial data. The key metrics here are familiar: sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value. You’re essentially asking, “Is the tool still performing the specific task it was approved for with the same level of accuracy?” It’s a passive, confirmatory process.

A “continual machine learning” model is a completely different beast. It’s designed to evolve and adapt as it ingests new data. This introduces incredible power but also significant risk, like model drift or the amplification of biases. Here, monitoring has to be active and ongoing. It’s not enough to just check for adverse events. The manufacturer needs to be watching for subtle shifts in performance, which could signal a problem long before it causes patient harm. Metrics would have to include not only clinical accuracy but also data drift detection—are the new patient data inputs significantly different from the training data? You’d need to conduct periodic revalidation against a benchmark dataset and maintain robust controls over the data pipeline. This is where a one-size-fits-all approach fails; the surveillance for a dynamic, learning system has to be just as dynamic itself.

The American Hospital Association noted the “black box” nature of AI, arguing that manufacturers should manage postmarket monitoring. What specific steps should vendors take to fulfill this responsibility, especially to support rural hospitals that lack resources for their own AI governance?

This is a crucial point, and I fully agree with the AHA’s position. Placing the burden of monitoring on hospitals, particularly smaller or rural ones, is simply not feasible. These facilities often lack dedicated data scientists or AI governance committees. For them, a new AI tool can feel like a black box they are asked to trust implicitly. To fulfill their responsibility, vendors need to move beyond just selling a product and start providing a service of ongoing trust and transparency.

A concrete first step is for manufacturers to provide a clear, intuitive performance dashboard for their clients. This shouldn’t require a Ph.D. to interpret. It should visualize key metrics in real-time: accuracy, usage rates, and any detected drift. Secondly, vendors must establish proactive alert systems. If the algorithm’s performance dips below a certain threshold or if it encounters a demographic it wasn’t adequately trained on, the hospital should be notified immediately with clear guidance on what to do. For a rural or critical access facility, this support is paramount. It could mean offering dedicated technical liaisons who can explain what the data means and work with the clinical team, ensuring the technology is a helpful assistant, not an opaque and potentially risky new burden.

Patient advocates want performance metrics to include “lived experiences” like care delays or mental distress. How can manufacturers realistically capture these qualitative patient burdens in their surveillance systems, and what would that reporting process look like step-by-step?

This is a paradigm shift from thinking only about clinical accuracy to considering the human impact of the technology. And it is entirely achievable. The first step is for manufacturers to collaborate directly with patient advocacy groups, like the Light Collective, to co-design patient-reported outcome measures, or PROMs, specifically for AI interactions. We can’t just assume we know what to ask. We need to hear from patients about what matters: the confusion, the anxiety from a contradictory result, the frustration of needing extra tests to validate an algorithm’s finding.

Once these tools are developed, the process would look something like this: Step one, integrate these simple surveys into the patient journey. After an AI-driven report is generated and discussed, the patient could receive an automated, secure message through their patient portal asking a few targeted questions about their experience. Step two, the manufacturer would be responsible for collecting and analyzing this anonymized data, looking for trends. For example, does a specific AI tool consistently score high on causing patient confusion, even if its diagnostic accuracy is high? Step three, this “experiential data” must be included in the performance reports shared with both the FDA and the healthcare providers using the tool. It reframes the definition of a successful device. A tool that is technically precise but emotionally destructive for patients isn’t a success; it’s a design failure.

Given the conflicting feedback, how can the FDA create a regulatory middle ground? What would a balanced framework look like that satisfies providers’ and patients’ calls for transparency without imposing the “duplicative requirements” that industry groups fear will stifle innovation?

The path forward is not a single road but a multi-lane highway, with lanes designed for different levels of risk. The FDA can create a middle ground by embracing the risk-based approach championed by industry but embedding the transparency and accountability demanded by providers and patients within it. For low-risk, locked AI devices, the existing regulatory frameworks within the Quality Management System are likely sufficient. This respects the industry’s position and avoids creating unnecessary, duplicative hurdles for simpler technologies.

For higher-risk or adaptive learning systems, however, the FDA should mandate a more robust plan as part of the premarket submission. This would be a “Postmarket Monitoring and Transparency Plan” where manufacturers must explicitly detail how they will track performance, monitor for bias, and, crucially, how they will communicate these findings back to hospitals and the public. This isn’t a new, separate regulation so much as a required component of the existing one. It directly addresses the “black box” concern by making transparency a condition of approval. This framework satisfies the call for manufacturer responsibility without inventing a whole new set of rules from scratch, instead building accountability directly into the well-established pathways to market.

What is your forecast for the future of AI device regulation, considering the rapid evolution of technologies like generative AI and the divergent feedback the FDA is currently receiving?

My forecast is that we are moving toward a future of dynamic, tiered regulation that mirrors the technology itself. The FDA understands that a rigid, static set of rules will be obsolete the moment it’s published. Instead, I predict we will see the agency develop a flexible framework that classifies AI devices not just by clinical risk, but also by their level of autonomy and adaptability—the locked vs. continual learning distinction will become a formal regulatory category. For emerging technologies like generative AI, the FDA will have to create new evaluation metrics focused on risks like “hallucinations” or the generation of biased or factually incorrect clinical notes, which are fundamentally different from the risks of older predictive models.

Ultimately, the non-negotiable element will be transparency. The era of vendors selling “black box” solutions and expecting hospitals and patients to simply trust them is ending. The feedback the FDA has received makes it clear that postmarket monitoring is not an optional add-on; it is a core responsibility of the manufacturer. The future of regulation will be built on the principle that if a company wants to put an adaptive, learning algorithm into the healthcare system, they must also provide the tools and the data to prove it remains safe, effective, and equitable every single day it’s in use.