With us today is James Maitland, a leading expert on U.S. healthcare policy and the intricate dynamics of the health insurance industry. We’re delving into the aftermath of a recent, fiery congressional hearing where lawmakers confronted the CEOs of the nation’s largest insurance companies. The session brought to light the deep-seated tensions over affordability, care denials, and a system many feel prioritizes profit over patients.

During recent hearings, insurance CEOs pointed to hospitals and drug companies as the main drivers of high costs. How valid is this argument, and what role do insurers’ own business models, like vertical integration, play in the affordability crisis? Please provide some specific examples.

It’s a classic case of pointing fingers, and while there’s a kernel of truth to their argument, it’s a deeply misleading oversimplification. Of course, the costs of new drugs and consolidated hospital systems are major factors driving up spending. But to position insurers as mere victims of these forces is disingenuous. Their own business models are profoundly shaping the landscape. Look at UnitedHealth and CVS. These aren’t just insurance companies anymore; they are sprawling healthcare empires that own pharmacies, physician groups, and the pharmacy benefit managers that negotiate drug prices. This vertical integration creates a closed loop where they can profit at multiple points in a patient’s journey, which doesn’t always translate to lower costs for consumers.

Companies like CVS and UnitedHealth now own insurers, pharmacies, and physician groups. While executives claim this integrated model benefits consumers, critics argue it drives up costs. What are the real-world consequences of this consolidation? Share some metrics or scenarios illustrating the impact on patient care and spending.

The consequences are enormous, and they often contradict the rosy picture the executives paint. The claim is that integration creates efficiency, but the reality can be the opposite. For instance, data shows that physician groups and pharmacies owned by an insurer are often paid higher rates than independent ones. A CEO like David Joyner from CVS can stand before Congress and say this model “works really well for the consumer,” but what does that really mean on the ground? It can mean your plan steers you toward their own doctors and their own pharmacies, limiting your choice. As Representative Ocasio-Cortez pointed out, it creates a system where the insurer gets a cut, the PBM gets a cut, the pharmacy gets a cut—and at the end of that chain, as she put it, “the patient gets screwed.”

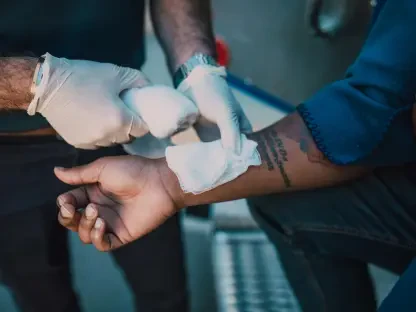

With research showing nearly one in five in-network claims on ACA marketplaces being denied—and most appeals being successful—some lawmakers suggested this is a business strategy. What operational factors lead to such high initial denial rates, and what specific steps could insurers take to reform this process?

When you see a figure like 19% of in-network claims being denied, and you pair it with the fact that most appeals are successful, it’s hard not to conclude that it’s more than just an administrative error. It truly looks like a business model built on attrition. The operational factor is an incentive to say “no” first. They create complex, often automated systems that flag claims for denial based on intricate rules, knowing full well that many patients and doctors will be too exhausted, confused, or intimidated to fight back. To reform this, insurers need to simplify their prior authorization processes, invest in more sophisticated clinical review systems that aren’t just automated gatekeepers, and, most importantly, change the internal metrics that reward cost-cutting over patient care. They must fundamentally shift from a model that bets on wearing people down.

One nonprofit insurance CEO stated the healthcare system has put profits ahead of patients and needs “tough love” from the government. What makes this perspective so rare among industry leaders, and what specific government actions could provide the “clear direction” he called for?

That statement from Paul Markovich of Ascendiun was so powerful because it was a moment of unvarnished truth from inside the fortress. It’s rare because the leaders of the for-profit giants are beholden to shareholders and Wall Street, where the primary directive is maximizing returns, not public health outcomes. Markovich, leading a nonprofit, has a different mandate. The “tough love” he mentioned could come in several forms. The government could enact and enforce much stricter regulations on vertical integration to break up anti-competitive monopolies. It could mandate transparency in pricing across the board, from PBMs to hospitals. And it could create a standardized, simplified process for claims and appeals that removes the insurer’s ability to use complexity as a weapon against patients.

Lawmakers from both parties expressed frustration with the insurance industry, yet investors seem unconcerned, with stock prices remaining stable. What accounts for this disconnect between political pressure and Wall Street’s reaction?

This disconnect is fascinating, and it boils down to one thing: Wall Street doesn’t believe that the political theater will translate into meaningful, system-altering legislation. Investors have seen this playbook before. They hear harsh words like “unconscionable” and “criminal,” but they see a deeply divided Congress that struggles to pass any significant reforms. The stocks for companies like UnitedHealth and CVS actually trended up during the hearings. This suggests investors are betting that the fundamental profit drivers—rising premiums, an aging population needing more care, and the power of their consolidated businesses—are insulated from the political outrage of the day. The financial incentives are just too powerful and entrenched for a few tough hearings to shake them.

A representative who was a former pharmacist criticized a CEO for his detached tone when discussing care denials, noting the difficulty of delivering that news to a patient. How does the corporate culture at large insurance firms contribute to this disconnect from the patient experience on the ground?

That moment was incredibly telling. Representative Buddy Carter, speaking from his 40 years of experience as a pharmacist, captured the immense gap between the boardroom and the pharmacy counter. The corporate culture at these massive firms is built on spreadsheets, risk-analysis models, and financial projections, not on the visceral, human experience of illness. A CEO like Stephen Hemsley can offer a measured, deferential “I appreciate the topic,” because for him, it is a topic. For the patient and the pharmacist, it’s a moment of fear, frustration, and sometimes, desperation. This culture creates a buffer of abstraction that allows executives to discuss denials in a detached way, because they are not the ones who have to look a sick person in the eye and explain why a faceless entity has decided their prescribed care won’t be covered.

What is your forecast for healthcare affordability?

My forecast, unfortunately, remains pessimistic in the short term. The fundamental pressures driving costs upward are not abating. National health spending is already at $5.3 trillion and is growing faster than the overall economy, which is simply unsustainable. With the enhanced ACA subsidies expiring, we’re about to see a sharp, painful shock for millions of families, with about 4 million people expected to lose coverage entirely. While the political rhetoric is heating up, the kind of seismic policy changes needed to truly bend the cost curve and untangle these massive, vertically integrated companies face immense political and financial opposition. I believe we will continue to see incremental changes and heated debates, but true affordability will remain elusive until there is the political will for the “tough love” and clear, decisive action that Mr. Markovich called for.