A sheriff’s knock over dinner and a court summons for a few hundred dollars may not sound like the front lines of a health care crisis, yet in towns across Kansas that is exactly where families find themselves when routine medical bills slip into collections and then into court. The sums at issue are often modest—balances that might be confused with a co-pay or a deductible—but the consequences can snowball into fees, interest, and wage garnishment, setting off a cycle that affects how people seek care and how hospitals keep doors open. This has become common enough to reflect more than poor communication or individual hardship; it reveals the precarious financing of rural health systems that rely on thin margins, large shares of public insurance, and small administrative teams to do work that urban systems spread across departments. In court filings, interviews, and charity care data, a picture emerges of hospitals treating lawsuits as a tool of survival while patients describe a legal machinery that feels out of proportion to the debt.

Human Stakes: A Small Bill, A Big Shock

In Medicine Lodge, a family with insurance and four children watched dinner turn into paperwork when the county sheriff delivered a lawsuit for a $230 balance tied to their local hospital. The husband had been traveling for work, missing a wave of phone calls and letters; the wife sorted through explanation-of-benefits forms and balance notices that blended jargon with fragmented amounts. Confusion hardened into anxiety as a deadline loomed, and what might have been a simple adjustment became a time-consuming quest for clarity. The experience felt less like a health provider seeking a solution and more like a creditor imposing a penalty, leaving a household that had done most things “right” wondering what they had missed. Their story tracked what many insured families describe: a mishmash of bills and insurance notices, unclear charity options, and a sudden escalation when the system’s patience ran out.

The emotional tenor of such moments is easy to dismiss from a spreadsheet but difficult to ignore at a kitchen table. Small towns run on relationships, and a hospital’s presence carries civic weight—it is employer, safety net, and first responder. When that institution arrives via court officer, the shock is amplified by a sense of betrayal, even if staff later offer payment plans or hardship reviews. In interviews, families emphasized not just the money, but the message: health care had shifted from neighborly help to legal coercion. That shift alters behavior long after a suit is resolved. Parents delay specialist visits for a child’s recurring asthma. A farmer waits out chest discomfort until harvest ends. Households build a habit of avoidance, trained by a system that seemed to greet financial hiccups with summonses rather than solutions.

How Widespread the Suits Have Become

Data points from district courts and hospital spokespeople show that these are not isolated skirmishes. In Emporia, Newman Regional Health filed 2,648 lawsuits in 2024, averaging about seven cases a day, and roughly one-fourth sought less than $500. Elsewhere, Hays Medical Center sued 1,041 residents over six years, a scale that hints at steady reliance rather than sporadic necessity. In Seward County, Southwest Medical Center filed 3,012 suits in a county of roughly 22,000 people, suggesting a legal cadence that touched a significant slice of local households. Over four years, Pratt Regional Medical Center brought 657 cases. Statewide totals were hard to tally because of fragmented databases and variations in how records are indexed, but the rhythm of filings across rural counties signaled a system leaning heavily on the courts to manage receivables.

That rhythm matters because small-dollar cases carry outsized consequences. Filing fees, service costs, and court interest can push a $300 balance toward double, even before a judge orders a payment plan or authorizes wage garnishment. Many defendants do not appear in court, either from confusion or work conflicts, leading to defaults that are quick to enter and hard to undo. Legal aid attorneys described patterns in which a forgotten imaging bill or a misapplied insurance adjustment cascaded into judgments affecting credit, employment verification, and landlords’ assessments. Critics argue that the volume of cases, combined with the concentration of low-balance claims, points to a collections culture rather than a true last resort. Hospital leaders counter that the pattern reflects a harsh arithmetic: too many accounts, too little slack, and too few alternatives that keep facilities solvent.

Why Hospitals Say They Sue—Even for Small Amounts

Executives at rural facilities describe a narrow path between fiscal prudence and community mission. Newman Regional’s leadership has cited negative operating margins, limited reserves, and a service area where poverty weighs on every budgeting decision. The hospital reported more than $8 million in uncompensated care last year, split between free care and sliding-scale discounts, and pointed to payment plans, interest-free loans, and bank-backed financing as options offered before legal escalation. Administrators say they reduced filings by tightening workflows and improving outreach, yet insist that collections, including small sums, remain necessary to avoid deeper cuts. For hospitals with few profitable service lines, “every dollar” is not rhetoric but daily practice, and small balances multiplied across thousands of encounters become material to keeping emergency rooms staffed and surgical suites open.

There is also a behavioral argument that reverberates in small communities. Attorneys who represent hospitals say ignoring low-dollar accounts signals that bills under a threshold are optional, a message that can spread quickly through word-of-mouth and social media. The result, they argue, is a slide in voluntary payment that punishes those who do pay and pushes institutions closer to service reductions. To counter that, legal teams outline multi-step delays—weeks with collections agencies, further pauses before filings—to give patients time to call, negotiate, or document hardship. The stated goal is not punishment but consistency: a transparent policy applied to every account to avoid accusations of favoritism and to set expectations that medical bills, like utility bills, require follow-through. Critics question whether the policy is transparent if many patients still do not know assistance exists.

What Advocates and Legal Aid Report on the Ground

Patient advocates see a different pattern: a communication failure dressed up as enforcement. Kansas Legal Services attorneys and former hospital billing specialists describe bills and portals that mention “financial assistance” in small type, websites where charity care links are hard to find, and phone staff who focus on collecting rather than counseling. Nonprofit hospitals are required by the IRS to publish and implement financial assistance policies, yet advocates say eligible patients often do not learn they qualify unless they ask the right question, to the right person, at the right time. When a call goes unanswered or a letter is misrouted, balances are treated as ordinary receivables rather than screened as potential charity cases. By the time agencies and attorneys are involved, trust is exhausted and paperwork hurdles feel insurmountable to families already juggling work, childcare, and health challenges.

Collections attorneys push back by describing layered reviews: hospital screening, agency verification, and legal team discussions about ability to pay before suits are filed. They cite timelines that stretch roughly 240 days from first bill to courthouse, with additional waiting periods after referral to counsel. Yet advocates argue the lawsuit volumes themselves are disproof that screening is robust or that communication is clear. They point to defendants who brought pay stubs and tax returns to court showing incomes well within charity thresholds, only to learn after judgment that discounts were possible. In their view, what is labeled “noncompliance” often reflects capacity limits—small billing offices processing thousands of claims—and a design flaw in how assistance is presented. People rarely act on what they cannot see, and many never saw help until it was too late.

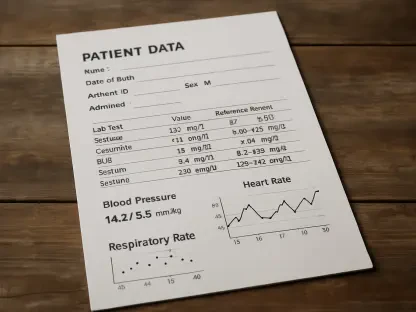

Charity Care, By the Numbers—and What It Implies

Tax filings offer a window into how hospitals convert charity policy into practice. As a share of operating expenses, charity care varied widely in recent years: Pratt Regional Medical Center reported 0.16%, Hiawatha Community Hospital 0.88%, Community Memorial Hospital in Marysville 1.01%, Hays Medical Center 0.73%, Coffeyville Regional Medical Center 1.64%, and Stormont Vail in Topeka 2.34%. On paper, these percentages suggest that similarly sized communities can arrive at very different outcomes, influenced by policy design, patient mix, and administrative capacity. Large systems note that small percentages can still equal large dollar amounts—HaysMed reported $77 million in charity care across six years—yet the disparity raises questions when hospitals with low charity shares are also among the most litigious.

These differences are more than accounting curiosities; they shape whether everyday bills are resolved quietly or become legal disputes. Facilities that emphasize early counseling, automatic presumptive eligibility using income proxies, and streamlined applications tend to resolve more accounts before collections. Others, constrained by staffing or financial stress, may set tighter criteria or rely on patients to navigate forms without help, producing lower recorded charity care and more debts labeled as bad or delinquent. The resulting picture is a patchwork across Kansas: one hospital applying discounts at registration, another steering patients to third-party financing, a third filing suit after short payment windows. For patients who cross county lines for care, the rules can shift with the ZIP code, creating an inconsistent experience that undermines confidence in the system.

The Rural Hospital Math That Drives Collections

Behind these choices sits a structural equation that rarely balances. Rural hospitals serve more Medicare beneficiaries and rely more heavily on Medicaid than urban peers. Reimbursements from those programs often do not cover the full cost of care, leaving gaps that private insurance traditionally helped offset. However, rural areas have fewer commercially insured patients, limiting that cross-subsidy. Meanwhile, fixed costs for essential services do not shrink with volume. An emergency department must be staffed 24/7; anesthesia and imaging require specialist coverage; regulations mandate readiness even on quiet nights. Urban hospitals absorb those overheads across high throughput and diverse service lines. Rural facilities face the same requirements with fewer patients, fewer profitable procedures, and less negotiating leverage with insurers.

State policy layers on additional strain. Kansas did not expand Medicaid, a decision that left more residents uninsured or underinsured and increased hospitals’ exposure to bad debt. While federal and state programs have offered targeted relief and demonstration projects for rural stabilization, hospital leaders describe a treadmill: grants expire, staffing costs climb, payer mix worsens as populations age, and revenue remains flat or dips. Administrative capacity is a critical limiter. Urban systems can field financial counseling teams that call patients pre-procedure, estimate out-of-pocket costs, and help enroll them in coverage or assistance. Rural billing offices often consist of a handful of employees juggling claims, denials, authorizations, and patient calls, with little time to coach someone through a charity application. Collections, in that environment, can feel less like strategy and more like gravity.

What Lawsuits Mean for Patients and Communities

For households, the legal process is an amplifier. A bill of $350 becomes a court matter that demands time off work, transportation, and a level of paperwork literacy that many do not possess. Missed hearings lead to default judgments; judgments lead to wage garnishments or liens; and those, in turn, affect credit and housing. Surveys suggest many families cannot absorb an unexpected $500 expense without borrowing or skipping essentials, so even small medical debts create cascading trade-offs: rent versus repayment, prescriptions versus utilities, filling the tank versus covering interest. People who have experienced collections describe a lasting shift in behavior, avoiding local hospitals for fear of another legal letter. That avoidance is not abstract; it means chest pain left to “watch and wait,” a dermatology biopsy postponed, or a follow-up skipped after a complicated delivery.

The community effects reach beyond individual stress. When medical debt becomes a public hazard, people enter the health system later and sicker, increasing the complexity and cost of care. Rural closures compound the problem. Analysts have ranked Kansas among states with the highest share of at-risk rural hospitals, with a significant fraction labeled at immediate risk. When a facility shuts down, travel times expand and certain services disappear entirely, forcing patients to drive hours for addiction treatment, dialysis, or labor and delivery. Research links closures to higher mortality from time-sensitive conditions and to higher prices at remaining hospitals as market power concentrates. From the viewpoint of a rural administrator, lawsuits can seem like a grim hedge against that outcome. From the perspective of residents, they can look like the system turning on the people it exists to serve.

How the Collections Pipeline Works

Hospitals describe a process designed to offer off-ramps before court. It begins with insurance adjudication and the first patient statement, often accompanied by eligibility checks that flag likely charity cases using address, household size, or credit proxies. If balances linger, accounts move to collections agencies that call, text, and mail notices, sometimes re-evaluating for assistance and offering installment plans. Legal teams come in later, adding another round of letters, repayment offers, and waiting periods; one attorney cited a 42-day pause after referral and a cumulative timeline of about 240 days from service to filing. Hospitals say interest-free plans are available in-house, with low-interest bank financing offered as a backup, and that hardship accommodations can be granted upon request. On paper, the pipeline contains multiple chances to avoid court.

In practice, outcomes hinge on visibility and bandwidth. Patients who pick up the phone early can secure $25-per-month plans or qualify for retroactive discounts. Others never see the relevant notice or do not recognize its significance amid insurance codes and duplicate bills from physician groups. Language barriers, unstable housing, and shift work complicate contact. On the hospital side, lean teams may not have the capacity to triage every account for assistance or to make repeated, personalized outreach. The sheer scale—thousands of encounters per month—pushes reliance on standardized letters and vendor workflows. Advocates contend that the number of lawsuits points to a pipeline that defaults to legal resolution too often, particularly for those who would have qualified for charity care. Hospitals respond that the pipeline reflects reality: limited resources deployed across community needs too extensive to handle case by case.

Policy Levers and Practical Fixes

There is no single reform that resolves both hospital fragility and patient vulnerability, but several paths could shift incentives. Expanding Medicaid would lower the uninsured rate and reduce bad debt, a direct relief valve for rural balance sheets. Short of that, lawmakers could limit the collateral damage of medical debt by restricting its use in credit scoring and curbing wage garnishment or property liens for medical judgments. Regulators could require clearer charity care disclosures—large-font notices on every bill, plain-language summaries at discharge, and standardized applications. Federal rural transformation funds, if secured and sustained, could underwrite shared financial counseling hubs that small hospitals cannot build alone. On the ground, facilities can make assistance unmistakable, train clinical and billing staff to raise it proactively, and adopt presumptive eligibility tools that grant discounts based on income data already available, reducing paperwork friction.

The next steps for Kansas looked pragmatic rather than dramatic: publish unmissable charity care terms, standardize no-interest payment plans with hardship tiers, and report metrics on screenings, plans, and lawsuits so communities could see what worked. Hospitals that piloted regional shared services for counseling and eligibility saw fewer accounts escalate and fewer small-dollar suits, a model that could be scaled with modest funding. Industry groups and consumer advocates agreed that early, clear engagement beat courtroom resolutions on cost and outcomes. The path forward also depended on targeted state support and careful use of federal programs to buttress rural operations while longer-term payer fixes were debated. Taken together, these moves signaled that suing over $300 balances had been a symptom, not a strategy, and that durable solutions rested on redesigning communication and financial assistance before the first bill ever reached a mailbox.