With the FDA’s recent approval of a novel device-based therapy for pancreatic cancer, we’re witnessing a fascinating convergence of physics, biology, and patient care. To unpack the significance of this milestone, we’re joined by James Maitland, an expert in robotics and IoT applications in medicine. Today, we’ll explore the real-world patient experience with this electric field technology, delve into the nuances of its clinical trial results, and consider the commercial and future therapeutic landscape for this innovative approach to oncology.

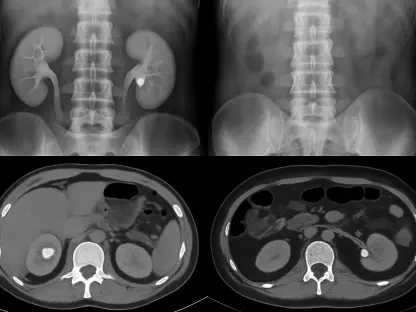

This therapy delivers electric fields via adhesive patches on the torso, a different application than its use in brain cancer. Could you walk us through the daily patient experience with this device and explain the key technical challenges in targeting pancreatic tumors this way?

Absolutely. The patient experience is a fundamental shift from traditional systemic therapies. Imagine wearing a set of adhesive patches on your torso, connected to a portable device that you carry with you. It’s a constant, low-intensity therapy working in the background. This is quite different from the skull-based application for brain tumors, and it presents a unique engineering puzzle. The primary challenge is anatomical. The pancreas is nestled deep within the abdomen, surrounded by other organs. Delivering a precise, effective electric field that disrupts cancer cell division without significantly affecting surrounding healthy tissue is incredibly complex. The system has to be robust enough for daily life while precisely targeting a tumor through layers of tissue, which is a significant bioelectrical engineering feat.

The clinical data showed a two-month gain in overall survival but no change in progression-free survival. What does this specific outcome suggest about the therapy’s mechanism, and why is the significant improvement in pain-free survival particularly meaningful for this patient population?

This is a fascinating and crucial point in the data. Seeing an improvement in overall survival without a corresponding change in progression-free survival suggests the therapy might not be shrinking tumors in the way chemotherapy does, but rather altering the biology of the disease to make it less aggressive. The electric fields disrupt the cancer cells’ ability to proliferate and repair themselves, potentially making them more vulnerable to the accompanying chemotherapy over the long term. This leads to a longer, more stable disease state. For patients with pancreatic cancer, a disease often accompanied by debilitating pain, the increase in pain-free survival from 9.1 months to 15.2 months is profoundly important. It’s not just about adding time; it’s about adding quality, functional time to their lives, which is an endpoint that I believe we’ll see valued more and more.

With an initial market of about 15,000 U.S. patients, this approval represents a crucial step in diversifying beyond brain cancer. What are the most critical steps for ensuring physician and patient adoption, and what commercial lessons can be applied from previous expansions into other cancers?

Gaining traction in a new indication is always a multifaceted challenge. The first critical step is education. Oncologists are accustomed to pharmaceutical and radiation-based treatments; a device-based therapy requires a new way of thinking about integration into the care plan. Novocure will need to provide robust support for clinics and patients to manage the device. The second step is demonstrating a clear value proposition beyond the clinical data, focusing on that significant improvement in pain-free survival. Commercially, the lesson from their previous expansions into mesothelioma and lung cancer is clear: diversification is a slow build. Despite those earlier approvals, brain cancer remains their core business. This pancreatic cancer approval, targeting a market of 15,000 U.S. patients, must be positioned not just as an add-on, but as an essential component of a new standard of care to achieve meaningful commercial growth.

Looking ahead, research is underway for treating first-line metastatic pancreatic cancer. What are the primary biological and logistical hurdles in applying this technology to metastatic disease compared to locally advanced tumors, and what would a positive result in that trial signify for the treatment landscape?

The leap from locally advanced to metastatic disease is substantial. The primary biological hurdle is the systemic nature of the disease. Tumor treating fields are a local therapy; they are delivered to a specific area. When cancer has spread, you face the challenge of where to direct the field. Do you target the primary tumor, the largest metastatic sites, or rotate the field placement? Logistically, this becomes far more complex for both the physician to prescribe and the patient to manage. However, if the trial, with data expected in 2026, shows a positive result, it would be a paradigm shift. It could suggest the therapy has a systemic or abscopal effect, potentially by making cancer cells more recognizable to the immune system. A win in the metastatic setting would fundamentally alter the treatment algorithm and elevate this technology from a niche application to a mainline therapy in oncology.

What is your forecast for the role of tumor treating fields in solid tumor oncology over the next five to ten years?

I believe we are at the beginning of a significant new pillar in cancer treatment. Over the next decade, I forecast that tumor treating fields will become an integrated component of combination therapies for a range of solid tumors, moving beyond last-line treatment options. We’ll likely see smarter, more efficient devices with improved algorithms to better target tumor beds and perhaps even adapt to a tumor’s response in real-time. The real breakthrough will be in synergy—understanding how these electric fields can best be combined with chemotherapy, targeted agents, and especially immunotherapies to create a more potent, multi-pronged attack on cancer. It represents a move towards a more personalized, physics-based approach to oncology that complements our existing biological and chemical strategies.