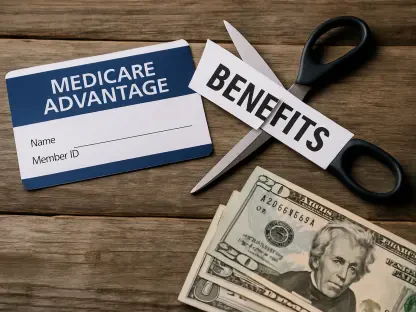

The familiar model of medical billing, where a patient receives a statement only after a direct consultation or procedure, is undergoing a significant transformation that is catching many consumers by surprise. Hospitals and primary care practices are increasingly implementing “Care Coordination” billing codes, effectively shifting their revenue model toward a subscription-like service without explicit patient enrollment. This means individuals, particularly seniors on fixed incomes, may find themselves billed for services rendered outside of a physical appointment, such as the time a clinical team spends managing their health records or coordinating care. These charges, legally supported by recent Medicare Physician Fee Schedule updates, are intended to compensate providers for “longitudinal care”—the ongoing management of a patient’s health over time. However, for the patient, these new fees can appear as an unexpected and recurring expense for simply being a patient at a particular practice, leading to confusion and financial strain.

1. The Emergence of New Billing Codes

The most frequently encountered new charge stems from Chronic Care Management (CCM), a service applicable to patients with two or more chronic conditions, such as diabetes, arthritis, or heart disease. Under this framework, medical practices are permitted to bill Medicare approximately $60 to $80 each month for the ongoing management of a patient’s case, which can include activities like prescription refills, chart reviews, and communication between specialists. While the practice receives the bulk of this payment, the patient is responsible for the standard 20% coinsurance on this Part B service. This translates to an additional monthly out-of-pocket expense of about $12 to $16. For many, this charge can appear on their statements indefinitely, often without a clear understanding that they have been enrolled in a program or that they possess the right to opt out. This silent enrollment turns routine care management into a recurring subscription fee that can accumulate significantly over the course of a year.

Another subtle yet impactful change to medical bills is the implementation of the add-on code G2211, which allows physicians to charge an additional fee for office visits that are part of a continuous doctor-patient relationship. This code is designed to reimburse doctors for the added cognitive load and complexity involved in treating a patient whose extensive medical history they know well. The code adds approximately $16 to the total allowed amount for the visit, and the patient is responsible for their portion of this increased cost through their regular coinsurance or deductible. In effect, this system can financially penalize patient loyalty, making a standard checkup with a trusted primary care physician more expensive than a visit to an urgent care clinic where the provider has no prior knowledge of the patient’s health. This counterintuitive outcome challenges the conventional wisdom that building a long-term relationship with a single doctor is the most cost-effective approach to healthcare.

2. The Digital and Administrative Shift

The convenience of digital communication with a doctor’s office, once a complimentary service, has now become a billable event at many major health systems. Patient portal messages, particularly those that require a degree of “medical decision making” from the provider, are now being classified as “Digital E/M” (Evaluation and Management) services. A simple query about a new symptom, a question about a medication’s side effects, or a request for a prescription renewal can now trigger a charge. These fees can range from $30 to $50 or more, depending on the perceived complexity of the medical advice required. For patients with high-deductible health plans, this cost is paid entirely out-of-pocket until their deductible is met. This policy introduces a financial barrier to communication, forcing patients to weigh the potential cost before asking for medical guidance and potentially delaying necessary care or advice.

Further complicating the billing landscape is the introduction of “Advanced Primary Care Management” (APCM) codes. These bundled payments are designed to provide practices with a more predictable revenue stream for comprehensive care coordination services. Unlike the more stringent requirements of older codes, APCM billing does not always necessitate detailed time-tracking, such as the 20-minute-per-month minimum often associated with CCM. For the patient, this can result in a vague line item on their bill, often labeled simply as “Care Management Services.” The broad definition of what these services entail makes them difficult to understand or dispute. In essence, the charge covers the general availability and background work of the patient’s care team, turning the concept of accessible primary care into a monetized service that is billed automatically, regardless of direct patient interaction during that billing period.

3. Navigating Consent and Taking Action

A significant issue with these monthly fees is the way patient consent is obtained. Federal regulations typically require a patient’s agreement before these recurring charges can be billed, but this consent is frequently integrated into the extensive annual paperwork patients sign. A standard “General Consent to Treat” form, often completed at the beginning of the year, may contain a clause that authorizes the practice to provide and bill for care coordination services. Patients, focused on the immediate reason for their visit, are unlikely to scrutinize these dense documents and may unknowingly agree to ongoing fees. Practices seldom provide a verbal explanation of the coinsurance implications or the recurring nature of the charges. Consequently, the enrollment is activated silently, and the patient’s first indication of this new financial obligation is the arrival of an unexpected bill for a service they did not explicitly request.

Understanding the Recourse Available

It was crucial for patients who identified these unexpected fees to recognize they had the right to halt them. The recommended first step involved contacting the doctor’s billing office directly and asking pointed questions about enrollment in Chronic Care Management or APCM programs. Once enrollment was confirmed, a clear and direct statement of intent to “disenroll immediately” was necessary. Medical practices were obligated to cease billing for the monthly service upon the revocation of consent. For most patients, particularly those who did not frequently use services like after-hours nurse lines or require intensive case management, the out-of-pocket expense of these programs often outweighed the benefits. Proactively managing one’s medical bills and questioning unfamiliar charges became an essential skill for protecting a personal budget from the quiet expansion of these subscription-based healthcare models.