A routine visit for a new pair of glasses or a preventative screening can take an unexpected turn when the intake form or a clinician begins asking about ethnicity, marital status, or housing stability. For many, these questions feel deeply personal and irrelevant to the immediate medical issue, sparking confusion and a sense of an invasion of privacy. This common reaction highlights a fundamental gap between the patient’s perspective and the broader goals of modern medicine. The reality is that this line of questioning is far from arbitrary; it represents a critical component of a vast data ecosystem designed to advance medical science, improve public health outcomes, and, perhaps most surprisingly, enhance the quality of an individual’s own care. Answering these questions is less about satisfying administrative curiosity and more about contributing to a collective knowledge base that fuels medical discovery and healthcare innovation for everyone.

The Bigger Picture of Public Health

When a patient provides demographic and personal information, they are contributing a small but vital piece to a “giant puzzle of data” that serves a purpose far beyond their individual chart. Once aggregated and anonymized, this information allows researchers and public health officials to see the bigger picture of community health. By analyzing data from thousands or even millions of patients, they can identify emerging patterns, track the spread of diseases, and uncover significant health disparities among different populations. This broad, data-driven perspective is essential for answering foundational questions such as who gets sick, where they get sick, and why certain groups are more vulnerable than others. This knowledge forms the bedrock of effective, large-scale health interventions, enabling healthcare systems to allocate resources more equitably and design public health campaigns that target the communities most in need, ultimately moving medicine from a purely reactive practice to a more proactive and preventative one.

Clinical data alone, such as lab results, diagnoses, and vital signs, often provides an incomplete story of a person’s health. To understand the root causes of complex conditions, healthcare professionals must look beyond biology to the “social determinants of health” (SDOH). These are the non-medical factors in the environments where people are born, live, learn, and work that profoundly affect health outcomes. A powerful illustration of this is seen in research on preeclampsia, a dangerous high blood pressure condition during pregnancy. Studies have revealed that Black mothers are diagnosed at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts, a disparity that cannot be explained by purely biological factors. Researchers now understand that race itself is not a biological risk factor, but that systemic racism—which manifests in issues like historical redlining, school segregation, and environmental inequities—is a powerful social determinant. Therefore, to build accurate predictive models for conditions like preeclampsia, data on a patient’s ZIP code, food security, or history of homelessness becomes indispensable, providing essential context about their life experiences and exposure to risk.

Diverse Applications Fueling Medical Discovery

The seemingly irrelevant questions asked during a check-in often have direct and powerful research applications across various medical fields. For instance, a cardiologist inquiring about marital status is not being intrusive but is contributing to studies that explore why single mothers, for example, have a higher likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease compared to their married counterparts. This data helps researchers uncover the complex interplay between social and economic pressures and their tangible impact on physical health. Similarly, when an optometrist collects data on race, it aids in investigating potential links between specific medications, such as certain weight-loss drugs, and adverse side effects like vision loss that may disproportionately affect one demographic group over another. These findings can lead to the development of safer prescribing guidelines and more personalized treatment plans, demonstrating how a simple question on a form can ultimately prevent harm and improve patient outcomes on a national scale.

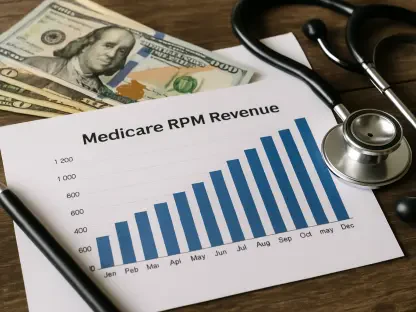

The large-scale collection of patient data from electronic health records has become instrumental in modern epidemiology and the management of chronic diseases. This rich repository of information has enabled health experts to track the prevalence of conditions like diabetes within specific geographic areas, predict the onset of dementia with greater accuracy, and even monitor the patterns of gum disease across different demographic groups. The utility of this data was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers were able to rapidly analyze patient records to determine which populations—based on race, geography, and insurance status—were being most severely affected by the virus. This critical information guided public health responses, from the targeted deployment of testing sites to the equitable distribution of vaccines. The same data continues to be a crucial resource for studying and understanding the complex, long-term effects of long COVID, showcasing the enduring value of this information in addressing both current and future health crises.

Balancing Privacy with Personalized Care

The legitimate concern over patient privacy is a cornerstone of the healthcare system, and the use of personal health data is not an unregulated free-for-all. Health information exchanges and research initiatives operate under strict protocols, with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) providing a robust legal framework for protecting sensitive information. For research purposes, datasets are almost always de-identified, meaning that personal identifiers like names and addresses are removed to protect patient anonymity. In many cases, studies only require limited information, such as birth dates and ZIP codes, to conduct their analysis. Furthermore, all research projects involving human data must undergo a rigorous approval process by an institutional review board (IRB). This independent committee ensures that the research is ethical, that participants are not harmed, and that all data is kept secure within firewalled networks, safeguarding it from unauthorized access and ensuring it is used responsibly for the advancement of medicine.

Beyond its value for future medical breakthroughs, the collection of personal information transformed the immediate care an individual received. When a patient indicated they had experienced food insecurity, for example, it allowed a physician to connect them directly with a nutrition program, which was often run by the hospital itself. A change in marital status from “married” to “separated” prompted a sensitive inquiry from a clinician about the patient’s well-being and whether they needed mental health or social support services. This process shifted the dynamic of data collection from a mere administrative task into a proactive opportunity for more holistic and responsive patient care. Ultimately, this approach equipped clinicians with the insights needed to see their patients as whole people, not just a collection of symptoms. This comprehensive understanding of a patient’s life and the unique factors influencing their health led to a more personalized and effective healthcare system for both the individual and society as a whole.