A startling revelation from a comprehensive analysis of U.S. insurance claims data indicates that the foundational diagnostic procedures for Myasthenia Gravis (MG) are being alarmingly overlooked, leaving a significant portion of patients without a definitive, lab-confirmed diagnosis. The study, which appeared in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences, found that less than half of all individuals newly identified with MG undergo the recommended serological blood tests considered the “gold standard” for identifying the specific autoantibodies that drive this complex autoimmune disorder. This gap is particularly concerning because the results of these tests are crucial for tailoring effective, personalized treatment strategies. Instead, a large number of patients are started on powerful MG-specific therapies, such as corticosteroids, based solely on a clinical assessment of their symptoms. This practice diverges from modern medical guidelines, which emphasize the importance of laboratory confirmation to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management, raising critical questions about the consistency and quality of care for those navigating this challenging condition.

The Diagnostic Disconnect

At the heart of the issue is a profound underutilization of essential diagnostic tools for a disease defined by its autoimmune nature. Myasthenia Gravis occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly produces autoantibodies that attack critical proteins at the neuromuscular junction, the vital communication point between nerves and muscles. The most frequent targets are acetylcholine receptors (AChR), though other proteins like muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) can also be involved. This assault disrupts nerve-to-muscle signaling, causing the characteristic muscle weakness and fatigue. While a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms is an important first step, serological testing is strongly recommended to confirm the presence and type of these autoantibodies. The study, analyzing data from 5,788 newly diagnosed MG patients between January 2018 and June 2022, revealed that only 44.7% received any MG-related antibody test. Compounding this, the use of electromyography (EMG), the most sensitive test for nerve function in MG, was exceptionally low, occurring in a mere 12.2% of cases, painting a clear picture of a diagnostic process that often falls short of established best practices.

Despite these significant gaps in confirmatory diagnosis, the initiation of treatment for Myasthenia Gravis was found to be remarkably widespread. The research indicated that a majority of all newly diagnosed patients, 69.5% to be exact, began at least one MG-specific therapy within a year of their diagnosis. Perhaps most troublingly, even among the more than 3,200 patients who had no record of ever receiving an antibody test, a substantial 63.4% were still prescribed treatments, predominantly corticosteroids and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. While patients who tested positive for the common AChR antibodies were, as expected, the most likely group to receive therapy (83.1%), the high rate of treatment among the untested population underscores a prevalent practice of relying on clinical suspicion alone. This approach, while potentially well-intentioned to alleviate symptoms quickly, proceeds without the benefit of definitive laboratory confirmation, creating risks of misdiagnosis, exposure to unnecessary side effects from potent medications, and delays in identifying the most appropriate therapeutic pathway for the individual patient’s specific form of the disease.

Disparities in Care and Access

A central and overarching trend identified by the research is the pivotal role of specialist care in ensuring proper diagnostic procedures are followed correctly. Patients whose initial MG diagnosis was made by a neurologist were more than twice as likely to undergo the recommended antibody testing compared to those diagnosed by non-neurologists, such as primary care providers or emergency room physicians. The data shows a stark contrast, with a testing rate of 54.8% for patients seen by neurologists versus just 33% for those diagnosed by non-specialists. This disparity highlights a significant variation in clinical practice and suggests that a lack of specialized knowledge may be a key driver of diagnostic omissions. The findings point to a critical opportunity for standardizing diagnostic protocols across all medical settings, ensuring that every patient, regardless of their initial point of contact with the healthcare system, has access to the same high standard of diagnostic evaluation that is essential for managing this condition effectively.

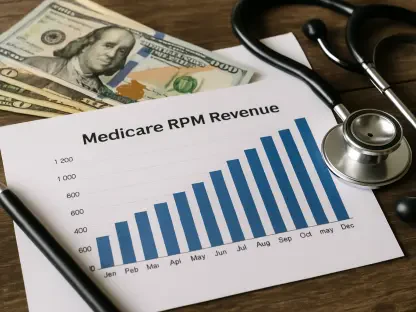

The analysis also uncovered several powerful socioeconomic and clinical factors that significantly influence whether a patient receives the proper testing. Statistical modeling revealed that patients with commercial insurance or Medicaid were less likely to be tested—by 18% and 32%, respectively—than those covered by Medicare. Geography also played a role, with individuals living in a rural area facing a 38% lower likelihood of undergoing serological screening. Other factors associated with a lower chance of testing included having a higher number of coexisting medical conditions and receiving the initial diagnosis in a more acute setting, such as an emergency department or during a hospital inpatient stay, rather than in an outpatient clinic. These findings suggest that systemic barriers, including insurance limitations, geographic isolation, and the complexities of managing multiple health issues, can prevent patients from receiving the complete and timely diagnostic workup that is recommended by experts.

Unpacking the Testing Patterns

Conversely, certain factors were associated with an increased probability of a patient receiving the necessary diagnostic tests. Beyond the crucial involvement of a neurologist, the presentation of classic MG symptoms was a strong predictor. Patients who exhibited symptoms such as double vision (diplopia), drooping eyelids (ptosis), or slurred speech (dysarthria) were significantly more likely to have their blood tested for MG-related antibodies. This suggests that physicians may be more inclined to order confirmatory tests when symptoms align closely with the textbook description of the disease. Furthermore, the data showed a procedural link: patients who underwent an EMG were 29% more likely to also have serological tests ordered. In an interesting demographic finding, Hispanic patients were 30% more likely to be tested than white patients, indicating that a complex interplay of clinical presentation and other patient factors can influence the diagnostic pathway.

Even among the minority of patients who did receive serological screening, the testing patterns revealed further opportunities for improvement. Of those tested, a slight majority (56.3%) were seronegative, meaning no MG-related autoantibodies were detected in their blood. Among the seropositive group, 42.4% tested positive for the most common anti-AChR antibodies, while a much smaller fraction tested positive for anti-MuSK (1.1%) or anti-LRP4 (0.2%). Critically, the study found that among the patients who tested negative, over half were only screened for anti-AChR antibodies. This limited testing panel leaves open the possibility that other autoantibodies, such as anti-MuSK, were missed entirely. This finding highlights a need not only for more widespread testing but also for more comprehensive testing protocols that include a broader panel of antibodies, especially after an initial negative result for AChR, to avoid misclassifying patients and to ensure every individual receives the most accurate diagnosis possible.

Charting a Course for Better Diagnostics

The research ultimately documented a substantial and concerning discrepancy between recommended diagnostic guidelines and the reality of clinical practice for Myasthenia Gravis in the United States. The evidence strongly suggested an urgent need to develop and implement standardized guidelines for both serological and neurophysiological testing to close this gap. Optimizing the diagnostic process, particularly by ensuring the early and consistent involvement of neurologists, was identified as an essential step toward confirming diagnoses with greater accuracy. Such improvements are fundamental to selecting the most appropriate and effective treatments, which in turn promises to improve the long-term health outcomes and quality of life for patients who live with this challenging autoimmune condition.