A critical disruption in Saskatchewan’s diagnostic imaging services has left numerous cancer patients in a state of prolonged uncertainty after the province’s only positron emission tomography scanner was forced into a sudden shutdown. The vital piece of equipment, located at Saskatoon’s Royal University Hospital, ceased operations for two full days just before Christmas and has since been running at only half capacity, creating a growing backlog of anxious patients who depend on its technology for essential diagnosis and treatment planning. This sudden failure has done more than just delay appointments; it has exposed the profound fragility of a centralized healthcare service and ignited a fierce debate about systemic preparedness, resource allocation, and the real-world consequences for individuals and families navigating life-threatening illnesses. The situation highlights a precarious dependency on a single machine and a solitary local supplier, a vulnerability that has now translated into significant emotional and potential medical repercussions for the province’s residents.

The Anatomy of a Diagnostic Failure

A Supply Chain on the Brink

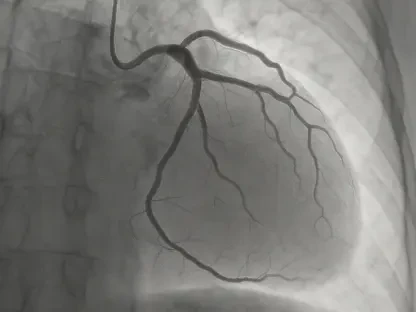

The core of the crisis originated not from a mechanical issue with the scanner itself but from a critical failure in its highly specialized supply chain. The entire PET imaging service hinges on the timely delivery of fludeoxyglucose (FDG), a radioactive tracer with an exceptionally short shelf life that is essential for the scans. On December 23, an “unexpected production issue” at the Sylvia Fedoruk Canadian Centre for Nuclear Innovation—the sole provincial supplier—abruptly halted the creation of this tracer. This single event triggered an immediate cascade effect, bringing the provincial PET service to a complete standstill. The delicate, just-in-time nature of the supply process meant there was no backup, leading to the immediate cancellation of 27 patient appointments over December 23 and 24 and plunging dozens of families into a state of deep uncertainty during the holiday season. The event underscored a significant vulnerability that had previously gone unaddressed, proving that the diagnostic chain was only as strong as its weakest link.

The immediate aftermath of the production failure left the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) scrambling for a solution. While services were completely suspended for two days, officials managed to secure a temporary and limited supply of the essential FDG tracer from Ontario, which allowed the Saskatoon scanner to resume operations on December 29. However, this stopgap measure has only been sufficient to run the machine at 50% of its normal capacity, a significant reduction that exacerbates an already growing waitlist. The SHA has been unable to provide a definitive timeline for when the Fedoruk Centre will resolve its production challenges or when the scanner will return to full functionality. This persistent lack of clarity has become a primary source of stress for patients whose treatment pathways are contingent on these scans, leaving clinicians to triage cases and prioritize the most urgent needs while many others are forced to wait indefinitely for answers about their health and future.

The Ripple Effect on Patients

The systemic breakdown is acutely felt in the personal stories of those affected, such as that of Erin Neufeld and her father, who is fighting lung cancer. His journey toward treatment was already fraught with delay, having waited two months for a PET scan that was a prerequisite for starting his therapy. The family’s hopes were crushed when his long-awaited appointment was abruptly canceled due to the tracer shortage. Neufeld’s account paints a vivid picture of the immense emotional toll this crisis inflicts, transforming a period that should have been focused on healing and strategy into one of heightened anxiety, frustration, and helplessness. For families like the Neufelds, the scanner’s operational status is not an abstract logistical problem but a deeply personal and urgent matter, where every delay feels like a setback in a life-or-death battle. Their experience serves as a poignant reminder that behind the statistics and official statements are real people grappling with the consequences of a fragile system.

Beyond the emotional distress, the service disruption forces families into difficult and often financially prohibitive decisions. Neufeld revealed her family is now contemplating traveling to Edmonton to seek a private scan, an alternative that comes with a hefty price tag of between $1,800 and $4,000, not including the additional costs of travel and accommodation. This situation highlights a troubling inequity in healthcare access, creating a potential two-tiered system where those with the financial means can bypass the delays in the public system while others have no choice but to wait. The necessity of even considering such an option underscores the desperation felt by patients and their loved ones. When the public system falters, the burden—both financial and emotional—is shifted directly onto the shoulders of the most vulnerable, forcing them to weigh their savings against the urgent need for timely medical care during what is already one of the most challenging times of their lives.

A System Under Scrutiny

Political Fallout and Calls for Accountability

The crisis has drawn sharp criticism from the Saskatchewan NDP, which frames the situation as an “appalling” and entirely predictable failure of government oversight and proactive management. Opposition MLAs Keith Jorgenson and Betty Nippi-Albright have voiced a consensus that this was not an unforeseeable accident but the inevitable result of a known vulnerability. Jorgenson poignantly compared the province’s reliance on a single, aging scanner to depending on an old, unreliable van for a critical journey, arguing that its weaknesses were well-documented, particularly following a similar shutdown in 2018. The opposition contends that the government has demonstrated a “lack of ability to anticipate problems,” allowing a critical piece of healthcare infrastructure to operate without necessary redundancies. This criticism goes beyond the immediate supply issue, pointing to a deeper, systemic failure to invest in and safeguard essential diagnostic services for the people of Saskatchewan.

Elaborating on this critique, the opposition highlighted the historical context that made this recent failure so frustrating. The 2018 shutdown, they argue, should have served as a definitive warning sign, prompting urgent action to bolster the province’s diagnostic capacity. Instead, years passed with little tangible progress. Nippi-Albright expressed deep frustration that more had not been done to secure and expand PET scan services in the intervening years, suggesting a pattern of reactive rather than proactive governance. Jorgenson drove the point home by emphasizing the grave danger posed by such delays, stating, “If I had one of the most deadly forms of cancer, I would not want to wait 70 days to start treatment.” Their collective message portrays the current crisis not as a new problem but as the culmination of years of inaction, which has directly resulted in unnecessary stress, anxiety, and risk for the province’s cancer patients.

Official Responses and Enduring Vulnerabilities

In response to the growing crisis and political pressure, the Saskatchewan Health Authority has maintained a focus on transparency and immediate mitigation efforts. Officials have been clear in their communications, attributing the disruption solely to the FDG tracer shortage from the Fedoruk Centre and not to a mechanical failure of the scanner itself. Their primary strategy has been to manage the drastically reduced capacity by implementing a triage system, prioritizing the most urgent cases to ensure that patients in the most critical need receive scans from the limited slots available. The SHA has also publicly stated its commitment to working closely with the Fedoruk Centre to resolve the production issue as swiftly as possible. However, this commitment has been overshadowed by the authority’s inability to provide a firm timeline for a return to full service, a crucial piece of information that patients and their families desperately need to alleviate their ongoing concern and uncertainty.

Ultimately, the event laid bare the profound and long-standing vulnerabilities within the province’s healthcare infrastructure. The crisis was a direct consequence of an over-reliance on a single PET scanner and a solitary local supplier, a precarious setup that created a critical single point of failure. This incident brought renewed attention to the long-promised second PET scanner for Regina’s Pasqua Hospital, a project for which a request for proposal was issued in August 2024 but which had seen little demonstrable progress since. The scanner disruption became more than just a logistical challenge; it served as a stark and painful illustration of what happens when critical healthcare systems lack the necessary redundancy and resilience. For the patients left waiting, it was a clear sign that the system designed to support them in their most vulnerable moments was itself in need of urgent care.