A critical breakdown in Saskatchewan’s healthcare services has left cancer patients in a state of distressing uncertainty after the province’s only Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanner was forced to operate at just half its normal capacity. The disruption, which followed a complete shutdown of the Saskatoon-based machine just before Christmas, has created a significant backlog for essential diagnostic procedures, delaying life-saving treatments and amplifying the anxiety of families already navigating a difficult diagnosis. This situation has cast a harsh spotlight on the fragility of the province’s medical imaging infrastructure, particularly as a long-awaited second PET scanner for Regina remains in the preliminary planning stages, offering no immediate relief to the hundreds of patients caught in the backlog. The reliance on a single point of service for such a crucial diagnostic tool has proven to be a high-stakes gamble with profound human consequences.

The Critical Role of Diagnostic Imaging

Positron Emission Tomography, often combined with a Computed Tomography (CT) scan, represents a cornerstone of modern oncological care, providing insights that other imaging technologies cannot. Unlike an MRI or a standard CT scan, which primarily visualizes the body’s anatomical structure, a PET scan illuminates metabolic function. By injecting a patient with a radioactive tracer, physicians can observe how organs and tissues are consuming energy. Since cancer cells are typically highly metabolic, they appear as bright spots on the scan, allowing for precise identification and location of tumors. This advanced capability is indispensable for accurately diagnosing various cancers, determining the stage of the disease, meticulously planning complex treatments like surgery and radiation, and effectively monitoring a patient’s response to therapy. As described by provincial officials, it is a truly “critical piece of equipment that helps in the diagnosis of a number of very, very life-threatening conditions.”

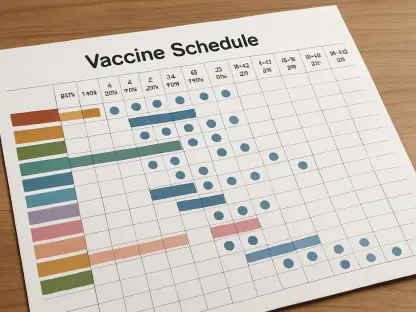

The current crisis underscores a severe vulnerability stemming from the province’s complete dependence on a single, aging machine located at the Royal University Hospital. First brought into service in 2013, the scanner has already experienced a similar shutdown in 2018, signaling a history of potential fragility. Despite these warnings, plans for a second PET scanner at Regina’s Pasqua Hospital have progressed at a sluggish pace. The government only issued a request for proposal in late August of 2024, and concrete details regarding its procurement, installation, and operational timeline remain unannounced. This lack of redundancy means that any disruption—whether mechanical or logistical—to the Saskatoon facility immediately affects the entire provincial population. Without a viable backup system, Saskatchewan’s capacity to provide timely, advanced cancer diagnostics hangs by a single thread, leaving patients and healthcare providers in a precarious position whenever that thread is strained.

A Human Toll Measured in Delayed Care

The profound human cost of this systemic failure is powerfully illustrated by the distressing experience of Erin Neufeld and her father, who is battling lung cancer. For two anxious months, the family had been waiting for the essential PET scan that would determine the stage of his cancer and clear the way for treatment to begin. They had endured the holiday season with the hope that the new year would bring clarity and a path forward. That hope was abruptly shattered when his appointment was cancelled on a Monday, with the family being informed that the scanner was down. Neufeld articulated the emotional devastation of this setback, stating, “We got through the holidays thinking and knowing that we were finally going to have the scan done and … the stage that we could get treatment started.” Her family’s story is a stark reminder that behind the statistics and logistical challenges are real people whose lives and well-being are directly impacted by these delays.

For families like the Neufelds, the crisis forces them to confront impossible choices. With the public system unable to provide timely care, some are left to consider seeking private diagnostic services out of province, a solution that is both costly and logistically challenging. Neufeld noted that traveling to Edmonton for a private scan could cost anywhere from $1,800 to $4,000 for the procedure alone. This figure does not account for the additional expenses of travel, accommodation, and time off work, placing an immense financial strain on families already grappling with the emotional and physical toll of a cancer diagnosis. This reality creates a two-tiered system where access to potentially life-saving diagnostics can depend on a patient’s ability to pay, an untenable situation that leaves many vulnerable individuals with no option but to wait and hope for the public system to recover, losing precious time in the process.

A Supply Chain Collapse at the Worst Possible Time

The Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) moved to clarify that the service disruption was not the result of a mechanical failure of the aging scanner itself but was instead caused by a critical breakdown in the supply chain for a necessary medical component. The issue stemmed from the production of fludeoxyglucose (FDG), a radioactive tracer with a very short shelf life that is essential for the vast majority of PET/CT scans. The province’s sole supply of this tracer is sourced from the Sylvia Fedoruk Canadian Centre for Nuclear Innovation in Saskatoon. On December 23, the center experienced an “unexpected production issue,” which instantly severed the supply of FDG to the hospital. This single point of failure in the supply chain had an immediate and cascading effect, demonstrating a profound lack of resilience in the province’s diagnostic infrastructure and leading directly to the cancellation of 27 patient appointments just before the Christmas holiday.

In response to the sudden halt in local production, the SHA was able to secure a temporary, emergency supply of FDG from a source in Ontario, allowing services to resume by December 29. However, this stopgap measure has proven insufficient to meet the province’s needs. The limited quantity of the tracer means the PET scanner can only operate at 50 percent of its normal capacity. This has forced the SHA’s imaging teams into a difficult triage process, prioritizing the most urgent and critical cases while working to reschedule all other patients. The ripple effect of this reduced capacity is a growing backlog and extended wait times for individuals whose conditions may worsen without timely diagnosis. The SHA has acknowledged the significant impact this is having on patients but has been unable to provide a definitive timeline for when the production issue at the Fedoruk Centre will be fully resolved and the scanner can return to its full operational capacity.

A System Under Scrutiny

The crisis has ignited sharp criticism from the provincial opposition, with NDP MLAs Keith Jorgenson and Betty Nippi-Albright accusing the government of a “lack of ability to anticipate problems.” They argue that the province’s over-reliance on a single, decade-old machine without a robust contingency plan is a clear failure in proactive healthcare management. Jorgenson drew a pointed analogy to illustrate the government’s inaction, stating, “If you’re driving around in a 30-year-old van and it keeps breaking, at some point, your employer should probably replace it.” Both MLAs described the situation facing patients as “appalling.” Nippi-Albright focused on the severe emotional toll, highlighting the “anxiety that families are going through” while waiting for critical diagnoses. Jorgenson directly connected the systemic failure to patient outcomes, noting, “If I had one of the most deadly forms of cancer, I would not want to wait 70 days to start treatment,” emphasizing the life-and-death stakes of these delays.

This incident laid bare the inherent risks of inadequate investment in healthcare redundancy. The crisis was not merely an unfortunate accident but a predictable outcome of a system lacking the necessary safeguards to protect against a single point of failure, whether in its equipment or its supply chain. The government’s failure to proactively establish a second PET scanning facility, despite years of advocacy and clear evidence of the existing machine’s age, left the entire province vulnerable. The experience of patients and their families highlighted the urgent need for a comprehensive review of critical healthcare infrastructure. Moving forward, the focus had to shift from reactive crisis management to strategic, long-term planning that prioritized resilience and ensured that essential diagnostic services were never again compromised by a single, foreseeable disruption.