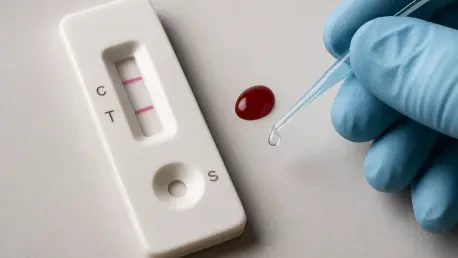

In the fight against malaria, a disease that plagues millions across Southeast Asia, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are often the first line of defense, especially in remote areas where advanced medical facilities are scarce. However, a widely used tool, the Abbott-Bioline malaria test, has come under intense scrutiny following a recent study by the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU), affiliated with Oxford University’s MORU Tropical Health Network. The findings suggest that this test may be failing to detect a significant number of infections, raising critical questions about its reliability. With approximately 4 million people affected by malaria annually in the region, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), the implications of an ineffective diagnostic tool are profound. This article delves into the heart of the controversy, examining the study’s alarming results, the real-world consequences for vulnerable populations, the test’s design challenges, the manufacturer’s stance, and the broader systemic issues at play in global health diagnostics.

Uncovering the Flaws: A Startling Study

The SMRU study, carried out between October 2024 and January 2025 along the Thailand-Myanmar border, has sent shockwaves through the public health community with its damning assessment of the Abbott-Bioline RDT. Researchers found that the test detected a mere 18% of Plasmodium falciparum infections, a particularly deadly strain, and only 44% of Plasmodium vivax cases. These detection rates fall dramatically short of acceptable standards, especially when compared to other RDT brands tested under similar conditions. The researchers concluded that the test is simply “not fit for purpose” in a region where malaria remains a significant burden. Such poor performance isn’t just a statistical concern; it represents a potential catastrophe for communities reliant on accurate diagnostics to initiate timely treatment. The study’s findings highlight a glaring gap in the tools meant to protect millions, prompting urgent calls for reevaluation of how such tests are deployed in high-risk areas.

Equally troubling is the context in which these results were uncovered, as the Thailand-Myanmar border is emblematic of the challenges faced in malaria-endemic zones. Here, health workers often operate in isolated settings with limited resources, making RDTs a lifeline for quick diagnosis. When a test fails to identify infections at the rates reported by SMRU, it undermines the entire framework of malaria control in Southeast Asia. The numbers—4 million affected annually per WHO estimates—add weight to the urgency of addressing this issue. Beyond the raw data, the study raises deeper questions about the validation processes for such critical medical tools before they reach the field. How could a test with such low sensitivity be in widespread use? This discrepancy between expected and actual performance demands a closer look at not just this specific product, but the broader mechanisms ensuring diagnostic reliability across diverse environments.

Deadly Risks: The Human Cost of Failure

The consequences of an unreliable malaria test are far from abstract; they translate into life-and-death scenarios for countless individuals. Professor Nicholas White, a co-author of the SMRU study and a tropical medicine expert at Mahidol University and the University of Oxford, emphasized the gravity of false negatives. In remote areas of Southeast Asia, where access to laboratories or hospitals is often hours or days away, a missed diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum can be fatal. This strain of malaria can progress rapidly, leading to severe complications if not treated promptly. When an RDT signals “no malaria” for an infected patient, the delay in care can result in tragic outcomes. This reality paints a stark picture of the stakes involved, as health workers in the field rely on these tests to make critical decisions without the backup of advanced medical infrastructure.

Moreover, the ripple effects of such diagnostic failures extend beyond individual cases to impact entire communities. In settings where malaria is endemic, inaccurate testing disrupts surveillance and control efforts, allowing the disease to spread unchecked. A false negative not only endangers the patient but also risks further transmission, as untreated individuals can continue to harbor and spread the parasite. This is particularly concerning in Southeast Asia, where dense populations and seasonal conditions like monsoons create ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes. The trust placed in RDTs as a cornerstone of malaria management is shaken when their reliability is called into question. Addressing this issue requires not just better tools, but also a renewed focus on supporting health systems in remote areas to cope with the limitations of current diagnostics, ensuring that no life is lost to a preventable oversight.

Practical Hurdles: Design and Usability Issues

Compounding the problem of low detection rates are significant design flaws in the Abbott-Bioline test that hinder its practical use. The SMRU researchers noted that even when the test does identify a malaria infection, the positive result often appears as a faint line on the test strip. In the challenging conditions of rural Southeast Asia—think monsoon rains and dim lighting in forested areas—such faint indicators are incredibly difficult to read accurately. Health workers, often operating under stress and with minimal training on nuanced result interpretation, may easily misinterpret or miss these subtle signs. This flaw transforms a diagnostic tool into a source of confusion, directly undermining its purpose of providing clear, actionable results in the field where clarity is paramount.

Additionally, the issue of faint lines isn’t an isolated concern but part of a broader pattern of usability challenges with RDTs, as pointed out by experts like Sunday Atobatele, a health and technology consultant with experience across multiple regions. Similar problems have been observed in other countries and with different test brands, suggesting a systemic gap in how these tools are designed for real-world application. Poor visibility of results can lead to errors in recording data, which in turn skews malaria surveillance statistics and hampers public health responses. In environments where every diagnosis counts toward tracking and controlling outbreaks, such design shortcomings are a critical barrier. The need for improved test readability, alongside better training for end-users, emerges as a pressing priority to ensure that diagnostic tools are not just technically accurate in controlled settings, but also practically effective where they are needed most.

Manufacturer’s Stand: A Conflicting Narrative

Abbott Diagnostics, the company behind the Bioline test, has mounted a firm defense against the criticisms leveled by the SMRU study. The manufacturer asserts that internal evaluations and testing conducted by a WHO-qualified laboratory confirm the test’s performance aligns with intended standards. Citing several published studies that support the product’s accuracy, Abbott maintains that the test functions as expected under proper conditions. Regarding the issue of faint lines, the company acknowledges the feedback and states it is actively exploring ways to enhance visibility. It also emphasizes that, per the product labeling, any visible line—however faint—should be interpreted as a positive result, a guideline communicated to customers and healthcare providers. This position, however, stands in stark contrast to the real-world challenges reported by field researchers.

This discrepancy between controlled testing environments and actual field conditions lies at the core of the debate surrounding the test’s efficacy. While lab results may show acceptable performance, the SMRU findings suggest that these outcomes do not translate to the harsh realities of remote Southeast Asian settings. The manufacturer’s insistence on proper usage guidelines raises questions about whether sufficient support and training are provided to health workers who must interpret results under less-than-ideal circumstances. Furthermore, the acknowledgment of faint lines as an area for improvement hints at an awareness of design limitations, yet it does little to address the immediate risks faced by patients misdiagnosed today. The clash between Abbott’s assurances and the on-the-ground evidence underscores a critical need for diagnostic tools to be evaluated in the specific contexts where they will be used, rather than solely in standardized lab settings.

Global Oversight: WHO’s Role and Broader Challenges

The World Health Organization has not remained silent amid the growing concerns over the Abbott-Bioline test and similar RDTs. Since August 2024, reports of false negatives and faint result lines have been on WHO’s radar, prompting a public notice in March 2025 to reinforce proper test usage and encourage incident reporting. A site inspection of Abbott Diagnostics’ manufacturing facility in Korea found no basis to remove the product from approved lists. However, with additional studies on test performance, cross-reactivity, and result interpretation expected by December 2025, the organization’s response is seen by some as cautious to a fault. Critics, including Professor White, argue that this measured pace fails to provide immediate guidance to countries grappling with unreliable diagnostics in urgent need of alternatives.

Beyond the specifics of this test, the situation reflects broader systemic challenges in global health diagnostics. The variability in RDT performance across regions—better results in some African studies versus poor outcomes in Southeast Asia—points to factors like environmental conditions, parasite strains, or manufacturing inconsistencies that are not fully accounted for in current approval processes. WHO’s observation of an “upward trend” in faint line issues across multiple brands suggests a widespread problem in test design and quality control. Addressing these gaps calls for stronger collaboration between manufacturers, researchers, and health authorities to ensure diagnostics are both scientifically sound and practically viable. Enhanced training for health workers, as well as stricter post-market surveillance, must also be prioritized to mitigate the risks posed by current limitations.

Path Forward: Addressing a Public Health Gap

Reflecting on the controversy surrounding the Abbott-Bioline test, it becomes evident that the struggle for reliable malaria diagnostics in Southeast Asia demands urgent attention. The SMRU study has exposed critical weaknesses, with detection rates that fall far below what is needed to protect vulnerable populations. The haunting reality of false negatives leading to untreated, potentially fatal cases underscores the human toll of these shortcomings. Abbott Diagnostics has stood by its product, citing lab-based validations, yet the gap between controlled tests and field realities remains a stark divide. Meanwhile, WHO’s ongoing evaluations have offered little immediate relief to those on the front lines.

Looking ahead, actionable steps must be taken to bridge this diagnostic gap. Manufacturers should accelerate improvements in test design, focusing on readability and sensitivity tailored to diverse environments. Global health bodies need to expedite context-specific testing protocols and provide clearer, faster guidance on reliable tools. Additionally, investing in training for health workers to navigate current test limitations could save lives in the interim. The path forward lies in collaborative innovation and accountability, ensuring that no patient in malaria-endemic regions is left at risk due to a preventable failure in diagnosis.