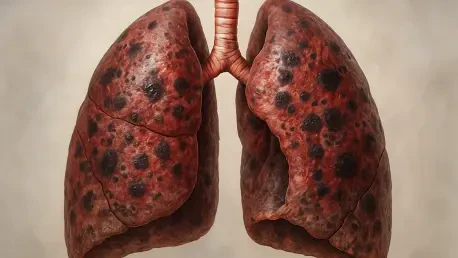

A recent retrospective observational study has illuminated a compelling and somewhat counterintuitive relationship within the complex pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), suggesting that higher levels of a specific white blood cell, the eosinophil, are associated with more favorable lung characteristics. The research, which leveraged quantitative computed tomography (CT) imaging and detailed pulmonary function tests, found that patients with elevated blood eosinophil counts demonstrated less severe structural lung damage and better respiratory function. This discovery, detailed in a paper published in BMJ Open, proposes that quantitative CT phenotypes could serve as a powerful complement to existing eosinophil-based risk stratification. By integrating these advanced imaging techniques, clinicians may be able to refine treatment strategies significantly, moving closer to a personalized “treatable-traits” framework for managing this debilitating respiratory condition and challenging previous notions about the role of these immune cells in lung health.

Investigating the Cellular Landscape

The foundation of this research was a meticulously analyzed cohort of 448 patients diagnosed with COPD at a tertiary hospital in China. This group was predominantly male (83%) with a mean age of 68.8 years, reflecting a common demographic for the disease. Investigators stratified these patients based on both the percentage and absolute count of eosinophils in their peripheral blood. The data revealed that 41% of individuals had eosinophil levels of 2% or higher, while 34% had absolute counts of at least 150 cells per microliter (µL). A smaller but distinct subgroup of 9% had even higher counts, exceeding 300/µL. An intriguing inverse correlation emerged with another type of white blood cell; patients with lower eosinophil levels consistently presented with higher neutrophil counts. Furthermore, these low-eosinophil groups were linked to a greater prevalence of chronic pulmonary heart disease, pointing toward a potentially more severe and distinct disease phenotype in the non-eosinophilic patient population and underscoring the disease’s inherent heterogeneity.

The stratification of patients by specific eosinophil thresholds was a critical element of the study’s design, allowing for a granular analysis of how varying levels of these immune cells correlate with disease characteristics. The chosen thresholds—2%, 150/µL, and 300/µL—are not arbitrary; they reflect clinically relevant cutoffs that are increasingly used to guide therapeutic decisions, particularly concerning the use of inhaled corticosteroids. By examining the patient data through these different lenses, the researchers were able to move beyond a simplistic, one-size-fits-all diagnosis of COPD. This method acknowledges that COPD is not a single entity but a syndrome with multiple underlying mechanisms and presentations. The findings strongly support the “treatable-traits” paradigm, an emerging approach that aims to identify specific pathological characteristics in individual patients—such as eosinophilic inflammation—and target them with tailored therapies. This precision-based methodology promises a more effective and personalized future for COPD management.

Visualizing the Structural Benefits

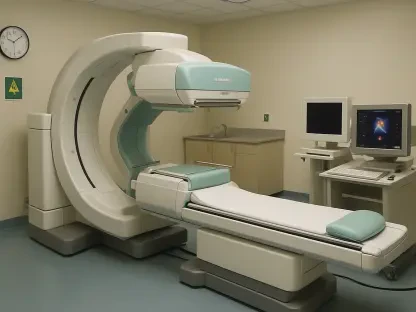

The use of quantitative computed tomography provided an objective and detailed window into the structural health of the patients’ lungs, revealing a clear pattern linked to eosinophil levels. Across multiple eosinophil thresholds, individuals in the higher strata consistently exhibited less bronchial wall thickening. Key metrics such as airway wall thickness, wall area percentage, and Pi10—a standardized measurement of airway integrity—were all significantly lower in patients with eosinophil levels at or above 2% or 150/µL. This association was even more pronounced at the highest threshold; Pi10 was notably reduced in patients with eosinophil counts of at least 300/µL compared to those with counts below 100/µL. These findings suggest that higher eosinophil counts are correlated with healthier, less inflamed airways, which is a crucial factor in mitigating the airflow obstruction that defines COPD. The data provides strong visual evidence that eosinophilic inflammation may not always be detrimental in this context.

In contrast to the clear benefits observed in the airways, the study’s findings on emphysema and the pulmonary vasculature were more nuanced and threshold-dependent. When patients were stratified using the more common 2% and 150/µL eosinophil thresholds, no statistically significant differences were observed in the overall emphysema index. However, a significant protective effect emerged at the highest eosinophil level. Patients with an absolute count of at least 300/µL demonstrated a markedly lower emphysema index, but this effect was specifically localized to the right upper lobe of the lung. This anatomical specificity suggests a complex interaction between high eosinophil levels and the processes that lead to the destruction of lung parenchyma. Meanwhile, the analysis of the pulmonary vasculature yielded no significant differences across any of the eosinophil strata. Parameters like the volume of small blood vessels and the total vascular network length remained consistent, indicating that the influence of eosinophils in this study was confined primarily to the airways and lung tissue rather than the circulatory system within the lungs.

Translating Structure to Function and Future Outlook

The structural advantages identified through CT imaging in patients with higher eosinophil counts were directly mirrored by superior performance in pulmonary function tests, confirming that these anatomical differences translate into tangible functional benefits. At the ≥2% eosinophil threshold, patients demonstrated a higher percent predicted diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), a key indicator of efficient gas exchange between the lungs and the bloodstream. At the ≥150/µL threshold, a more comprehensive profile of enhanced lung function became apparent. This group displayed lower residual volume and a reduced ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity, signifying less air trapping—a common and debilitating problem in COPD. These patients also showed a higher percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) and an improved DLCO. The correlation was strongest at the highest eosinophil count of ≥300/µL, where patients exhibited superior results across a broad spectrum of measures, including forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and maximal expiratory flow rates, underscoring a robust link between eosinophil levels and overall respiratory health.

This research ultimately concluded that higher levels of blood eosinophils in COPD patients were strongly associated with a milder disease phenotype, characterized by less bronchial thickening, reduced airflow limitation, and better gas diffusion capacity. The specific finding that an eosinophil count of at least 300/µL was linked to a lower emphysema index in a localized lung region highlighted the potential of quantitative CT to uncover the subtle heterogeneity within eosinophilic COPD. While the study’s conclusions were tempered by its single-center, cross-sectional design and a relatively modest sample size, its insights into the pathophysiology of COPD were invaluable. In a clinical landscape where blood eosinophil counts are increasingly used to guide therapeutic choices, this work demonstrated that quantitative CT phenotyping could offer essential, objective context. The alignment of a biological marker with precise structural imaging data equipped clinicians with a more powerful toolset, advancing the push toward a truly personalized medicine approach for managing COPD.