With the Department of Health and Human Services signaling a major push to accelerate artificial intelligence in healthcare, the industry is at a critical juncture. The agency’s recent Request for Information (RFI) isn’t just a survey; it’s an invitation to co-author the future of clinical care. To unpack what this means for innovators, providers, and patients, we’re speaking with an expert in health technology policy who has spent years at the intersection of regulation and real-world implementation. Our conversation will explore the most impactful levers HHS can pull—from overhauling legacy payment systems to clarifying the murky waters of regulation and liability—and the practical hurdles that need to be cleared for AI to truly transform patient outcomes.

The HHS RFI mentions three major levers: regulation, reimbursement, and R&D. In your view, which of these presents the biggest opportunity for accelerating AI adoption, and what initial, concrete step should the agency take within that area to build momentum?

That’s the central question, isn’t it? While all three are deeply interconnected, I firmly believe reimbursement is the most powerful lever HHS can pull right now. You can have the most brilliant R&D and the clearest regulations, but if providers can’t get paid for using a new technology, it will wither on the vine. The RFI itself points out the “inherent flaws in legacy payment systems,” and that’s not just bureaucratic language; it’s a massive wall to progress. A concrete first step would be for HHS to launch a pilot program for a new payment model focused on high-value AI. Instead of trying to fit AI into old fee-for-service codes, this model would reward the outcomes the AI helps achieve—like reduced hospital readmissions or faster, more accurate diagnoses. This would immediately signal to the market that HHS is serious about modernizing incentives and breaking the “inertia” that holds innovation back.

HHS wants a “predictable” regulatory posture for AI. Based on your experience, what specific actions would make the regulatory landscape less uncertain for innovators, and how can HHS balance the need for rapid development with ensuring patient safety and data privacy?

For innovators, “predictable” is the magic word. Right now, developing an AI tool, especially one that’s a non-medical device, feels like navigating a ship in a thick fog. You don’t know what standards you’ll be held to until you’re already far from shore. The most impactful action HHS could take is to publish a clear framework for evaluating these tools, both before they hit the market and after they’re deployed. This isn’t about adding red tape; it’s about providing a clear map. The key to balancing speed with safety is to make this framework “proportionate to any risks presented,” as the RFI suggests. A low-risk administrative AI shouldn’t face the same scrutiny as a high-risk diagnostic tool. By tiering the requirements, HHS can protect patients and maintain public trust without stifling the rapid innovation we desperately need.

The article notes that “inherent flaws in legacy payment systems” could diminish AI’s promise. Could you describe a specific payment policy change that would incentivize providers to adopt high-value AI tools and walk me through how that new model would work in a clinical setting?

Absolutely. Let’s imagine a specific model tied to a high-value AI intervention. Say there’s an AI tool that analyzes patient data to predict the risk of sepsis in the ICU with incredible accuracy. Under the old system, the hospital buys the software and that’s it—it’s just a cost center. A new, modernized payment model would create a bonus payment for every documented case where the AI led to early intervention that prevented a full-blown sepsis crisis. In a clinical setting, this would mean the system is no longer just another blinking light. The hospital would be financially motivated to integrate it deeply into the nursing workflows, train staff to react to its alerts, and track the data meticulously. This shifts the focus from just using technology to using it to achieve better, less costly health outcomes, which is the entire promise of AI in the first place.

Beyond policy, the RFI asks about administrative hurdles within healthcare organizations. From what you’ve seen, what is the most significant internal barrier to implementation, and can you share an example or metric that illustrates how this hurdle slows down progress?

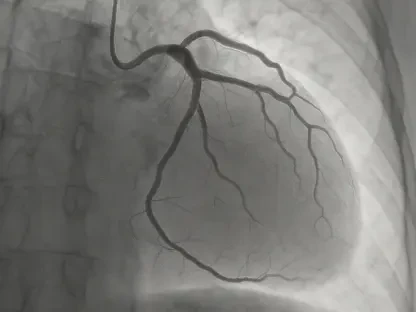

The single biggest internal barrier I see is workflow disruption and the resulting clinician burden. We have this vision of AI seamlessly helping doctors, but the reality is often clunky and frustrating. For example, a hospital might invest in a state-of-the-art AI radiology tool, but to use it, the radiologist has to log out of their primary system, open a separate application, manually upload the images, wait for the analysis, and then copy-paste the results back into the patient’s record. This adds five to ten minutes per scan. Even if the tool is brilliant, that friction is a deal-breaker for a busy professional. A key metric that shows this is “clinician adoption rate.” I’ve seen organizations where, six months post-launch, less than 20% of the intended users are actually logging in because the administrative hurdle is just too high. It illustrates that the best tool is useless if it makes a doctor’s life harder.

The department acknowledged novel legal issues around liability and privacy. What specific role do you believe HHS should play in establishing new governance and accountability structures, and what is one key piece of guidance they could issue to clarify these responsibilities?

This is a tangled web, and HHS shouldn’t try to be the sole judge and jury. Instead, its most effective role is to be a convener and a standard-setter, creating a safe harbor for responsible innovation. The agency can bring together developers, providers, insurers, and patient advocates to build consensus around new governance structures. A crucial piece of guidance they could issue is a “shared liability framework.” This document would outline clear principles for accountability. For instance, it could state that a developer is liable if their algorithm is proven to be faulty or biased, while a healthcare organization is liable if they implement the tool improperly, fail to train staff, or if a clinician overrules a correct AI recommendation without clinical justification. This clarity would do wonders to reduce the legal uncertainty that currently makes many organizations hesitant to adopt powerful new tools.

What is your forecast for the adoption of AI in clinical care over the next five years?

My forecast is one of pragmatic optimism, heavily dependent on how HHS responds to this RFI. We won’t see a sci-fi future of robot surgeons in every OR, but we will see a profound and rapid integration of AI into the background of care delivery. Expect AI to become standard for optimizing hospital operations, predicting patient risk scores, and significantly reducing the administrative burden that leads to burnout. We will also see more sophisticated AI tools assisting clinicians in interpreting complex data, from medical imaging to genomic sequencing. The adoption won’t be a tidal wave but rather a rising tide, lifting the capabilities of specific departments first. If HHS gets the reimbursement and regulatory pieces right, it will turn that tide into a powerful current, making AI an indispensable partner in care within the next five years.