The personal gadgets strapped to our wrists have undergone a quiet but profound transformation, evolving from simple pedometers into sophisticated health-monitoring platforms capable of capturing data once confined to the walls of a clinic. Modern wearables are now frequently equipped with advanced medical sensors, including electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood oxygen (SpO2) monitors, which effectively turn these devices into tools for continuous health signal tracking. This technological leap brings capabilities like on-demand ECG readings and the detection of heart rhythm irregularities, such as atrial fibrillation, directly to the consumer. This rapid advancement raises a central and increasingly urgent question: do these next-generation fitness trackers, with their array of new medical functionalities, truly justify their often significantly higher price tags? Answering this involves a deeper exploration into the real meaning of “medical-grade,” the intricate sensor technology at play, the scientifically validated accuracy of these features, and the inherent, real-world compromises that users must inevitably accept when they integrate this technology into their daily lives.

Understanding the Technology

Defining Medical-Grade

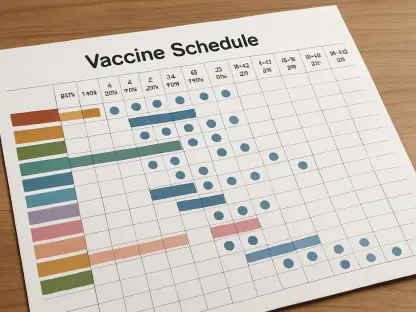

The term “medical-grade” is frequently used in the marketing of advanced wearables, but its meaning is more nuanced than it might initially appear. It often implies that a device’s hardware is constructed to more stringent standards than typical consumer electronics or, more commonly, that its software has received regulatory clearance for specific clinical applications. This approval is a critical distinction because it signifies that the manufacturer has submitted evidence, usually from clinical trials, demonstrating the device’s ability to perform a specific task with a reasonable degree of reliability, such as distinguishing an irregular heartbeat from a normal one. However, this regulatory green light comes with significant and important caveats. Official clearance for a particular function does not mean the device is a substitute for comprehensive medical diagnostics performed by a professional. For instance, a single-lead ECG on a smartwatch, while capable of flagging potential signs of atrial fibrillation, cannot provide the detailed, multi-angle view of the heart’s electrical activity that a standard 12-lead ECG in a clinical setting offers, which is essential for a full diagnosis. Therefore, while the “medical-grade” designation lends a degree of credibility to a feature, the data it generates is best viewed as a preliminary indicator that requires careful interpretation by a qualified healthcare professional within the broader context of a patient’s complete health history and other clinical findings.

Diving deeper into the regulatory landscape reveals that clearance is granted for highly specific use cases, not as a blanket endorsement of the device’s overall medical utility. A wearable might be cleared to detect signs of atrial fibrillation between 50 and 120 beats per minute, but it may not be validated for rhythms outside that range, which is a crucial limitation. The approval process itself involves demonstrating a certain threshold of performance against an established clinical standard, but this does not guarantee flawless accuracy in every real-world scenario a user might encounter. The data from these devices is most valuable when it serves as a catalyst for a conversation with a healthcare provider. A physician will use an alert from a wearable not as a diagnosis but as a single data point—a piece of a much larger puzzle that includes the patient’s symptoms, risk factors, and the results of more robust, clinical-grade diagnostic tests. The wearable’s information can be a powerful conversation starter, prompting individuals to seek medical advice they might have otherwise delayed, but it remains just one part of the comprehensive diagnostic process that is essential for proper medical care and treatment planning.

How the Sensors Work

The advanced health-monitoring capabilities of modern wearables are primarily driven by two core sensor technologies: electrocardiogram (ECG) and photoplethysmography (PPG). Electrocardiogram sensors function by detecting the very faint electrical signals that are naturally produced by the heart with every beat. On a wrist-worn device, this is typically a single-lead measurement, which is captured when the user intentionally creates an electrical circuit by touching a specific point on the device, such as the digital crown or a metal bezel, with a finger from their opposite hand. This action allows the device to record a snapshot of the heart’s rhythm over a short period, usually about 30 seconds. The primary application of this on-demand feature is to analyze the heart’s rhythm for irregularities, with the most common target being atrial fibrillation, a condition characterized by a chaotic and often rapid heartbeat. The strength of the ECG function lies in its ability to directly measure the electrical activity of the heart, which provides a more direct and often more reliable analysis of heart rhythm compared to methods that infer it from pulse data alone.

In contrast to the electrical-based ECG, features like heart rate and SpO2 monitoring utilize a light-based technology known as photoplethysmography (PPG). These sensors work by illuminating the skin on the wrist with light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and then measuring the amount of light that is reflected back to a photodetector. By analyzing the minute fluctuations in light absorption, which correspond directly to the pulsing of blood through the capillaries with each heartbeat, the device can accurately calculate the user’s heart rate. This same fundamental principle is cleverly adapted to estimate blood oxygen saturation (SpO2). By employing different wavelengths of light, typically red and infrared, the sensor can differentiate between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in the blood based on their distinct light-absorption properties. It is important to recognize that this “bounce-back” or reflective method used on the wrist is generally considered less accurate than the “pass-through” or transmissive method employed by clinical-grade fingertip pulse oximeters, where light passes through the finger to a sensor on the other side. Some trackers also leverage their PPG sensors to detect signs of atrial fibrillation by analyzing the irregularity of pulse timings over time, offering a passive monitoring alternative to the more direct, on-demand ECG function.

Balancing Potential with Practicality

Validated Benefits and Inherent Limitations

An overarching consensus from a growing body of scientific research and extensive real-world use is that while next-generation wearables possess a genuine and exciting potential for health monitoring, their accuracy and reliability can be highly variable depending on the device, the user, and the specific circumstances. Numerous studies have confirmed that some devices can effectively screen for certain health conditions, most notably atrial fibrillation. In some cases, this has led to the early diagnosis of “silent” cases in individuals who were otherwise completely asymptomatic, allowing for proactive medical intervention that could potentially prevent more serious complications like stroke. Similarly, tracking long-term SpO2 trends can offer valuable insights, such as monitoring a person’s acclimatization to high altitudes or identifying recurring patterns of nocturnal oxygen desaturation that might suggest the presence of sleep-disordered breathing, like sleep apnea. The primary and most significant strength of these devices lies not in providing a single, diagnostically precise, in-the-moment measurement, but rather in their ability to reveal subtle trends and patterns over extended periods, which can empower users and their doctors with a more holistic view of their health status over time.

However, the precision of these sophisticated sensors is subject to a multitude of interfering factors that can compromise data quality and lead to inaccurate readings. User motion is a primary culprit, as physical activity can introduce significant noise and corrupt the data from both ECG and PPG sensors, often resulting in inconclusive or erroneous results. The fit of the device on the wrist is also absolutely critical; a tracker that is worn too loosely will fail to maintain the consistent skin contact necessary for the sensors to function correctly. Furthermore, a substantial amount of research has shown that intrinsic physiological factors, such as darker skin pigmentation, which contains more light-absorbing melanin, can interfere with the accuracy of PPG-based measurements for both heart rate and blood oxygen levels. External conditions, such as the presence of bright ambient light, low skin perfusion due to cold temperatures, and even the specific placement of the sensor on the arm, can all influence the quality of the data collected. Consequently, while some high-end wearables perform well enough to provide genuinely useful health indicators under ideal conditions, others can be too inconsistent to be relied upon for any decision-making that requires a high degree of precision, highlighting the need for user awareness and caution.

Real-World Trade-Offs

The integration of advanced, continuously operating medical sensors into a compact, wrist-worn device introduces a series of practical trade-offs that users must carefully consider. Perhaps the most significant of these is the impact on battery life. Constant background monitoring of metrics like SpO2 or the analysis of heart rhythms for irregularities is a highly energy-intensive process that can dramatically reduce the time between charges. This reality forces users into an unavoidable compromise: they can either enable these powerful, potentially insightful features and accept the inconvenience of more frequent, sometimes daily, charging, or they can disable them to extend the device’s battery life to a more manageable duration. This trade-off can directly undermine the core value proposition of continuous, passive monitoring, as a device that needs to be charged every day may miss important data during the time it spends off the wrist. This friction point is a key aspect of the user experience and represents a significant practical limitation that prospective buyers must weigh against the potential health benefits offered by these advanced features.

Beyond the purely technical limitations, there is also a notable psychological component to wearing a device that constantly scrutinizes one’s health. Frequent, and sometimes inaccurate, alerts about potential heart rhythm irregularities or low oxygen levels can induce significant anxiety and stress, leading to a phenomenon known as “alert fatigue,” where the user becomes desensitized or overly worried by the notifications. This can prompt unnecessary and costly visits to a clinic, placing a burden on both the individual and the healthcare system. Conversely, the absence of an alert does not guarantee perfect health, as these devices can and do miss brief or intermittent issues, which could potentially create a dangerous false sense of security. It has become a prevailing viewpoint within the medical community that data from consumer wearables currently serves as a preliminary “nudge” or a supplementary data point rather than a definitive diagnostic tool. Physicians almost always require confirmation from a clinical-grade test, such as a Holter monitor or a full hospital ECG, before making a diagnosis or adjusting a treatment plan. The decision of whether a next-gen fitness tracker is worth the extra cost remains a personal one, weighing the potential for early health insights against the compromises of battery life and the understanding that these devices are a supplement to, not a replacement for, professional medical care.